If you prefer an alternative format you can listen to Alison reading Episode 3 on Soundcloud.

I tune into the satellite NOAA 19 from the edge of freshly ploughed fields in Arbroath, with a view of the Royal Marines Condor base, and strawberries growing in polytunnels. My ears are abuzz with static—it’s cold and windy and I’m distracted. Fuzzy lines streak across the sun-struck screen of my laptop. It’s been a long, dry few weeks of high pressure. The sky is rose-pink before the haar comes in at the beach early the next morning. The high pitched signal from NOAA 19 floats above the North sea and the static joins the crash of waves on a high tide: an ocean of static, an ocean of noise.[1] I had thought of the static as something to fight, now I let it sound, lean into the noise. On the horizon are oil tankers and the Bell Rock lighthouse. Someone litter picking asks if I’m listening for dolphins, and the sound draws attention from sandy-faced dogs.

*

‘The static's like the sound of thinking.’[2]

*

Back in Glasgow I start asking others to join me in my daily practice of sensing weather satellites and decoding images. To work through the static: think with me about adding to what open-weather call—in their video ‘Satellite Séance’—a ‘counter-geography borne of the magnetic state’.[3] What could this activity of connecting to a satellite-as-medium draw out for others; as a way to spend-time-with and underpin a conversation; in the places, atmospheres, and frequencies we listen to and share? What does it mean to séance: to draw in other voices—in discussion, writing, quotation—as I entwine myself with open-weather? Together we approach associative histories of other experiments with electromagnetic and radio fields, that draw out other voices from the ether. To think through these technologies and the sounds they produce asking: what might be their collective ‘spectral inheritance’.[4] These conversations interrupt and expand my understanding of open-weather: opening out from the specificities of the project to think about the potential of the aesthetic spaces it interacts with, and letting the static take over.

*

‘The connection of vibrating harmonies across space flowered easily into figures of interpersonal contact, and we now ordinarily speak of ‘being on the same wavelength’, ‘having a brain wave’, ‘tuning in’, ‘switching on’.[5]

*

Artist Rosie O’Grady joins me in our local park, swapping pre-work coffee for capturing a pass of NOAA 19. Rosie assembles the turnstile antenna and notes the similarity of its spindly arms to the theremin, a musical instrument she has been working with. Known for its eerie, uncanny wailing voice, it is played without physical contact—as though the sound is pulled from 'thin air'—using radio frequency oscillators. We talk about our experiences of operating a theremin and sensing for a satellite as both experiments with unseen forces: electric fields and radio waves. Our devices amplify their transmissions, allow us to hear and experience them: they become mediums our bodies interact with. Their effects were profoundly revelatory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and birthed ideas of the spectral; experiencing these effects ourselves builds an understanding of how much they transformed the world-view and imaginaries of that era. We reflect on the myriad additional presences and waves coursing through the air now: Bluetooth, WiFi, 3G, 5G et al.

I learn the theremin was the product of Soviet government-sponsored research into proximity sensors, invented in 1928 by military radio engineer Leon Theremin, ‘a master eavesdropper who would later be forced by the KGB to bug the US embassy in Moscow’.[6] The virtuoso theremin player, Clara Rockmore, heavily influenced Theremin’s design to increase the sensitivity and range of the instrument.[7] I learn more about her from watching the documentary ‘Sisters with Transistors’: advocating for her instrument as a valid ‘medium’ for expression to a wary establishment, Clara says the theremin evokes ‘the singing of a soul’.[8] In this record of the development of DIY electronic sound technologies and the women behind them, the spectral is central:

*

‘The spirit of modern life was a banshee, screeching into the future.’[9]

*

Artist Kirsty Hendry meets me the next day—as we listen to NOAA 19’s musical ticks and beeps from our DIY ground-station, passing the antenna between us, we talk about her research into the life of Scottish spiritualist Helen Duncan. I want to understand more what histories open-weather’s use of ‘séance’ brings forth. I delve a little deeper into the infamous Callander born medium, who I learn was the last in Britain to be tried and sentenced under the 1735 Witchcraft Act, where gender and class bias were instrumentalized both by the prosecution and the defense. I find a text by Marina Warner, where she describes Duncan as though a weather-maker, a receiver and a transmitter both:

‘Mrs. Duncan was celebrated in her lifetime for the clouds of shining, billowing spirit stuff that emanated from her as she sat in the spirit cabinet, groaning and shuddering as the trance state took hold. A medium’s body became a porous vehicle as the phenomena exuded from mouth, nose, breast and even vagina: she acted as a transmitter, in an analogous fashion to the wireless receiver, catching cosmic rays whose vibrations produced phantoms and presences.’[10]

Here, a woman’s body is described as acting as though a passive device, as a ‘porous’ communicator with an ability to be vulnerable and susceptible to invading spirits. The clairvoyant becomes receiving technology to make invisible forces visible. Instead of acting solely as a transparent medium (voicing out the ideas of others), revisiting these histories through the lens of open-weather, can we frame these women’s work as active and engaged? In Sasha’s words—sending ‘transmissions of political affinity’; using and connecting networks created by séance and electric innovations as means of dissemination:

*

‘As conduits for higher powers and more enlightened beings, historically mediums delivered public speeches and lectures at the spirits’ behest. I should point out to you that these spirits also happened to be passionate advocates for social justice, persuasive allies in the abolitionist and suffrage movements.’[11]

*

This history is contested and complicated, fragmented and known through subjective and emotional accounts. Kirsty shares a passage from Helen Duncan’s biography written by her daughter [12]: I read that in 1941, Duncan spoke with a deceased sailor from HMS Barham and conveyed to his mother that the ship had been sunk, although the War Office did not officially release this information until several months later. In 1944 one of Duncan’s séances was raided by police. Officers attempted to stop the cloud-like ectoplasm issuing to and from Duncan’s mouth, but failed. Whether she was summoning spirits or tapping into radio frequencies, intercepting government messages as a different sort of surveillance, either way the ectoplasm—as knowledge, or truth—came out.

*

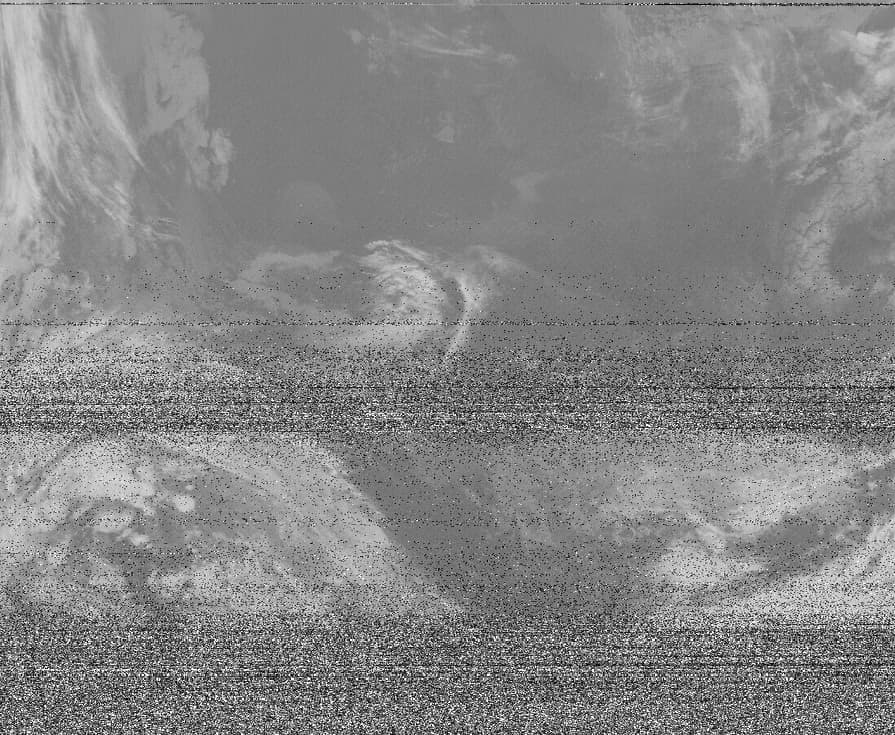

Through the open-weather ‘séance’ we connect with the unseen presences of orbiting satellites and radio waves to ‘materialise’ two images from the weather satellite: a visible light image and an infra-red image. The satellite roams the planet, locked into its polar orbit, and I wonder how many people are listening to its transmission, and where. The satellites we intercept are not passive voyeurs; they are the ‘eyes’ of the governments and commercial organisations that inflict the anthropocenic destruction they image. Outwith the bounds of these agencies, open-weather’s guides and open source software-based radio techniques offer access to otherwise expensive media that could fill the rooms of amateur radio enthusiasts. The open invitation allows a DIY network to build, and connections to grow between disparate people, with specificities of their dispositions and localities.

In Glasgow, when we process NOAA 19 sound recordings through the software, the satellite image emerges from the audio carried over radio waves, and we see familiar landmasses—partially obscured by weather. We are somewhere in there, too. Our arms were tired as we held out the antenna. Lines of hazy static mark where we passed it between us. We can see places we are not and access their weather. Snow on the Cairngorms. Ice sheeted Norwegian fjords. Cloud covered Iceland. Swathes of cold, dark sea in between. I can’t help but see the currents of light and shadow, the white billowing clouds, as ectoplasm writ across the screen.

***

[1] JR Carpenter, ‘Notes on the Voyage of Owl and Girl’ in ‘An Ocean of Static’ (Penned in the Margins, 2018) pg27

[2] Tom McCarthy, ‘C’ (Vintage, 2010) pg63

[3] Open-weather, ‘Satellite Séance’ (video, 2020)

[4] Open-weather, ‘Satellite Séance’ (video, 2020)

[5] Marina Warner, ‘Into Thin Air’ (London Review of Books, 2002)

[6] David Tompkins ‘How to Wreck a Nice Beach: The Machine Speaks’ (Melville House, 2010) pg89

[7] Making her debut with the theremin in 1934, for this performance she also arranged spirituals with Hall Johnstone for a black male sextet, later touring with baritone and political activist Paul Robeson from 1940-43.

[8] ‘Sister with Transistors’ (dir. Lisa Rovner, 2021)

[9] ‘Sister with Transistors’ (dir. Lisa Rovner, 2021)

[10] Marina Warner, ’ETHEREAL BODY: THE QUEST FOR ECTOPLASM, Seeing Is Believing’ (Cabinet Magazine, 2003) https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/12/warner.php

[11] Kirsty Hendry, ‘Navel Gazing: An Appendix’ in ‘Speaker Speaker’ (2020)

[12] Gena Brealey with Kay Hunter, ‘The Two Worlds of Helen Duncan’ (Saturday Night Press Publications, 2008)

***

Thanks to Kirsty Hendry and Rosie O’Grady.